TW: OCD, intrusive thoughts

When I was a little girl, I had a secret: I believed I wasn’t a real person.

Sure, I looked like a person. I could see that I had the same basic components as anyone else – hair, skin, eyes, a face – but it was the self beneath the surface that bugged me. One of my earliest memories is the sensation that everyone in the world spoke a language that I didn’t know. Everybody else knew when to laugh at the right moments and how to say the right things. Everybody else seemed able to converse easily, and I just… couldn’t.

No matter what I said or did, it seemed wrong in some undefinable way. So I watched other people closely, hoping that careful observation would teach me how to imitate a ‘normal human being’. No one else appeared to experience physical pain when confronted with certain lights or colours. No one else seemed to find eye contact violating or feel as though another person’s eyes were boring into the most intimate parts of their soul.

I learned to pretend that I didn’t feel that way either. I arranged my face into a careful mask of socially appropriate emotion. I tried to smile and laugh at the ‘right‘ moments, all the while thinking, ‘my laugh sounds fake. I talk like a robot. Any minute now, someone’s going to realise I’m not real.‘ I ridiculed myself for my own early experiences with sadness or anger, believing that even my emotions weren’t real. It wasn’t long before I developed the belief that I didn’t deserve to feel or express anything.

I don’t know what I thought would happen when other people discovered I wasn’t like them, but I lived in dread of being discovered. My parents were always kind and supportive, and you would’ve thought that would make me feel comfortable enough to confide in them. Yet, their kindness made me hide my feelings all the more. I didn’t want them to be disappointed when they realised that I wasn’t the ‘real‘ human child they’d hoped for.

The pressure to keep up the performance was exhausting so I developed rituals to comfort myself. I counted the cracks in the sidewalk, believing that if I counted all of them and landed on an even number, everything would feel right in my head. I scheduled every moment of my day. I colour-coded my crayons and dolls. I lined them all up in an order that could never be broken, believing that the slightest deviation from my rigid structure was on par with the apocalypse.

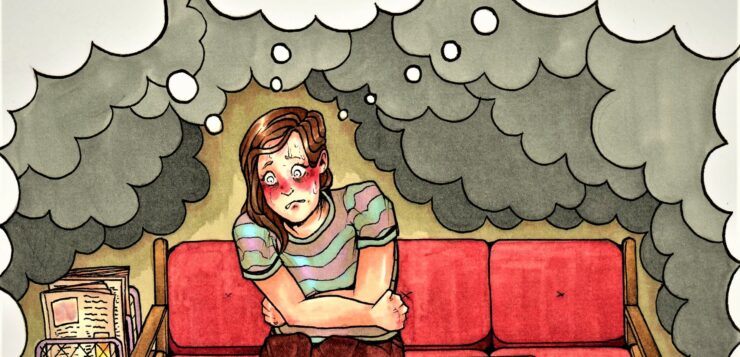

Once my obsession with organisation set in, the intrusive thoughts weren’t far behind. I became terrified that I would blurt out swear words in church or say something unkind to people I loved. I knew I didn’t want to do those things, but the fear that I might do so against my will was so powerful that I would often clap my hands over my mouth or dig my nails so sharply into the skin of my palms that I left deep crescent indentations behind.

As the years passed, I would often lose 8-10 hours of my day in silent, obsessive rumination, reviewing my exact words or actions in a feverish scrabble for certainty. I needed to know that I had not said or done something bad or offensive, and I became terrified of the possibility that I might have said or done the wrong thing. When I couldn’t find certainty in mental review, I went down a Google rabbit-hole to see if my worst fears made me a terrible person in the court of public opinion.

It never once occurred to me that I might have Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and I certainly didn’t think I might be autistic. I had only ever seen these conditions represented in movies like Rain Man and through off-hand comments like, ‘I’m so OCD!‘, to describe someone who liked to clean a lot. Far from envisioning a medical explanation, I had spent my life assuming that I was inherently broken and bad. I was 23-years-old before I realised there was a name for the hell in my head and that none of it was my fault. I was also shocked to learn that 92% of people who have OCD also battle at least one other disorder and that there is a high comorbidity rate between OCD and autism.

Today, I firmly believe that misrepresentation of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder played a significant role in my years of silent suffering. If I had known that OCD was more than washing your hands or liking a tidy house, I would have sought help earlier. As I’ve been more open about my struggles, I’ve learned that hundreds of other people have suffered, undiagnosed and untreated, for the same reasons. That’s why I want to reiterate that OCD is not a joke. OCD is not an adjective. It’s not a synonym for organised. OCD savaged my childhood and stole years of my life before accurate representation empowered me to seek help.

If you think you might have OCD, I hope my story can inspire you to pursue treatment. If you don’t have OCD, please think carefully about your words. You never know what someone is going through, and you never know how the misinformation you spread could impact their future.